Census faces challenges in Michigan, particularly in the north

By ZHOLDAS ORISBAYEV

Capital News Service

LANSING — Seasonal properties, vacant houses, the lack of internet, distrust of government and fewer census takers, not to mention the pandemic, are challenges to the 2020 U.S. census, especially in Michigan’s rural northern counties, census experts say.

This in-depth story was published in The Mining Journal, Lansing CityPULSE, Harbor Light, CLOSUP (UMICH), Michigan NonProfit Association.

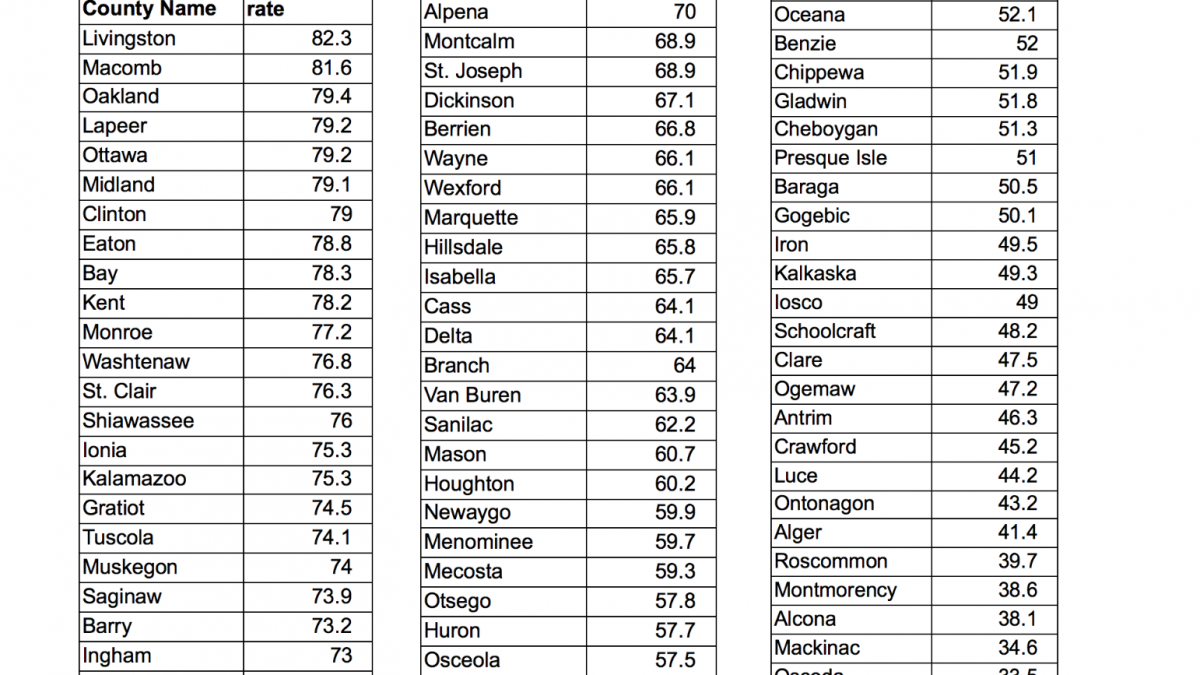

Statewide, about 71% of Michigan households self-reported their numbers online to the U.S. Census Bureau. That’s better than the national rate of 62.1%.

But the statewide number obscures low rates of self-response in the low-population rural north.

The lowest self-response rates by county in Michigan include Lake (27.3%), Keweenaw (29.9%), Oscoda (33.5%), Mackinac (34.6%) and Alcona (38.1%), according to the Michigan Statewide Census office.

But it’s difficult to know how many people are uncounted.

One reason for low self-reporting rates is that more than half of the homes in the north are seasonal or occasional use properties, and the people who live there part-time report their numbers from their permanent addresses, said Statewide Census Director Kerry Ebersole Singh.

Those households are still counted as potentially holding people until census takers can verify their status. Census takers have been visiting residences that did not self-respond since Aug. 11.

“There are more than 55,000 households, which represent 140,000 residents in Michigan, still to be counted on the 2020 census,” she said. That is an estimate based on Michigan’s average number of people per household.

U.S. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross has said he intends the 2020 census to end the field operations by Oct. 5, despite a preliminary injunction extending the deadline to Oct. 31 by U.S. District Judge Lucy Koh.

And some experts are skeptical of the accuracy of the bureau’s report that when you add homes counted by census takers the response rate balloons to 98.6% of Michigan’s housing units that have been counted.

“Despite the bureau’s best efforts, even in a less challenging environment, data collected during the door-knocking operation are less reliable than self-responses, which translates to less accurate census results,” said Terri Ann Lowenthal, a former staff director of a congressional census oversight subcommittee.

“We do not know how many Michiganders have been counted,” Lowenthal said. “We only know the percent of housing units, which may or may not be occupied, that have been ‘completed.’”

The pandemic is among the reasons, she said.

“Verification of unoccupied housing units needs more time and investigation than just one visit by the enumerator,” Lowenthal said.

The pandemic delayed field operations and enumerators could not confirm, as required, that some units were vacant April 1, she said.

Another problem is that the pandemic meant that census takers more often rely on someone else for household data or filling in missing answers with administrative records, she said. That can systematically omit groups such as kids and young adults.

And completion rates don’t account for the homeless or people living in transitory locations such as campgrounds, boats and motels.

Another source of error could lead to double counting. “Students, who were sent home because of the pandemic, might be counted in their homes, but they are supposed to be counted in the university location,” Lowenthal said.

Only 5% of local officials in Michigan expressed strong confidence in the accuracy of Michigan’s 2020 census count in a University of Michigan survey last spring.

“The survey of 1,342 local government officials found that those somewhat confident in the census dropped from 56% to 51%, and those who are not very confident or not at all confident increased from 30% to 34% over last year, said Thomas Ivacko, the executive director of the university’s Center for Local, State and Urban Policy.

The survey didn’t ask the reasons for the low confidence, Ivacko said. He said he assumed that lack of broadband internet access might be the key issue for people in rural northern counties.

Suspicion of the government is one reason people don’t respond, other experts say.

“In general, people believe that the government is too nosy and this information should be private,” said Joan Gustafson, a leader of the Be Counted Michigan 2020 census campaign. “Lack of understanding the importance of the census is also a leading factor for ignoring to be counted.”

Gustafson, an external affairs officer with the Michigan Nonprofit Association, said that neighborhoods and communities trust nonprofit organizations more than the government. That’s why her organization is helping explain the importance of the census.

The political consequences of undercounting Michigan residents is high as the census determines the distribution of the country’s 435 congressional seats, she said.

“Michigan lost two seats over the last two censuses and we are at risk of another seat at this time, which means Michiganders will have fewer representatives in Washington D.C., who protect their interests,” she said.,

Detroit had only a 50.5% self-response rate as of Sept. 28, while the other southern cities in Michigan self-responded up to 80%, according to the Statewide Census office.

“The reason why the response rate in Detroit is so low is that up to 100,000 house units out of all 380,000 residential addresses that filled in census data are vacant,” said Victoria Kovari, the Detroit 2020 Census Campaign’s executive director. “When the U.S. Census Bureau recalculates the response rate based on only occupied addresses after all field operations are finished, Detroit’s response rate should definitely go up, as they take out all of these vacant addresses.”

Kovari said that the campaign has spent close to $1 million to place ads in social, digital and traditional media to promote the importance of the census to communities since January.

“We have done over 100 events to get people to sign up for the census since June,” she said. “We have hired 12 community groups to do canvassing in Detroit areas of low response, and they have knocked almost 300,000 doors in the city of Detroit.”

Kovari said that another reason for a low confidence rate is fewer employees in the U.S. Census Bureau.

“A decade ago, Detroit had five census offices and this year we have only one,” she said. “The regional office for Michigan, Ohio and Indiana states was in Detroit, but now it’s in Chicago.”

“All of these factors have made counting challenging and led to an increase in people’s lack of confidence in census accuracy,” she said.